The winery at Château de Beaucastel

Wine Icons: Coudoulet de Beaucastel

I feel that if I was writing this ten years ago, Coudoulet de Beaucastel would be in my hidden gems section, not here. Back then Coudoulet was a bit of an industry secret, we all knew how good it was, and as a merchant if you saw it on a restaurant wine list you knew you were in safe hands.

When I was a student who knew nothing about wine beyond how to drink it one thing I was sure of when I arrived Friday afternoon in the corner shop was that I liked Côtes-du-Rhône, and I especially liked Côtes-du-Rhône when it had ‘Perrin’ on the label. Back then it was still ‘Perrin Père et Fils’ but now the fils part has grown up they call themselves Famille Perrin. They are the Southern Rhône’s ying to Chapoutier’s yang in the north: two large commercial outfits that maintain extremely high standards throughout their ranges, both as close to a guarantee of quality as you are likely to see on a bottle of wine.

The bedrock that the Perrin’s empire is built upon is Château de Beaucastel, undoubtedly one of the greatest names in Châteauneuf-du-Pape. The estate was purchased by Pierre Tramier 1909 and inherited by his son-in-law Pierre Perrin. Five generations later it is still in the same family and still setting the standard in Châteauneuf-du-Pape as one of its most iconic producers.

You would be forgiven for mistaking Coudoulet for Beaucastel’s second wine. It mimics the the same syntax you see on a lot of second wines, think Les Forts de Latour, Pensées de Lafleur or Echo de Lynch Bages. Second wines are traditionally made from vineyard parcels that do not quite make the cut during l’assemblage when the final blend for the Grand Vin is made. Usually they are plots of younger vines, or parcels from lesser terroirs, or ones that have underformed in any given year due to the vagaries of the growing season.

Coudoulet is less a second wine and more of an understudy to Château de Beaucastel, a precocious sibling that perhaps does not have the same gravitas and weight as its elder but nonetheless sparkles with its own light, not a shadow but a reflection.

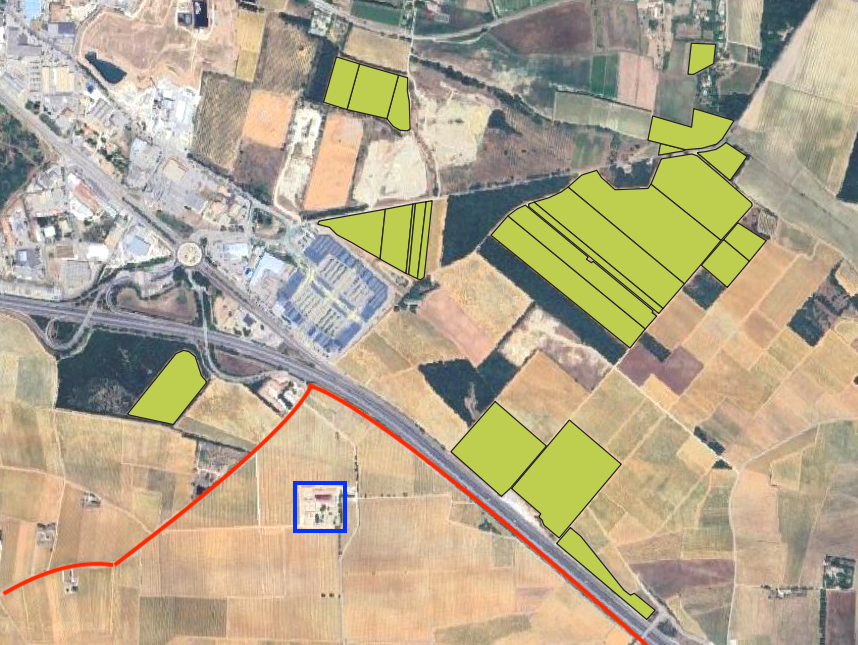

Its legend as ever with French wine comes from its vineyards and their terroir. They lie just beyond the lieu-dit of Châteauneuf-du-Pape, a stone’s throw, or more accurately a road’s-width, from Beaucastel’s own. That road is the A7 colloquially known as the Autoroute de Soleil, and, as as Marc Perrin memorably put when I tasted his wines with him, it makes a convenient marker for the map-makers but it does not signal the end of the Châteauneuf-du-Pape terroir.

The green plots are the parcels of vines that go into Coudoulet, the red line the lieu-dit of Châteauneuf-du-Pape with the vineyards of Beaucastel inside, with the blue marking Beaucastel’s winery

There is barely a change in the soil, perhaps not lying as deep as Beaucastel’s but with the same ancient molasse seabed with gacial deposits, covered with the regions famous galets roulés renown for their ability to trap heat during the day and bleed it back to the vines overnight. However Coudoulet is no Châteauneuf-du-Pape, it is just a humble Côtes-du-Rhône; but from a region with 84,000 hectares of vines, producing 3.3 million hectolitres of wine it is the greatest Côtes-du-Rhône you can buy.

There I said it out-loud. I didn’t even say ‘arguably’ for once. Of course the Rhône has it hierarchy, its Villages and its Crus, but of all the wine that is labelled as just Côtes-du-Rhône you will find none better, it is a hill I am prepared to die on. And there are plenty of Rhône reds with much grander titles and those heavy, embossed bottles they are so fond of in the region that are not a patch on Coudoulet.

Coudoulet’s 30 hectares of vineyards are organically farmed and the red is a blend of 40% Grenache, 30% Mouvèdre, 20% Syrah and 10% Cinsault. That high proportion of Mouvèdre wasn’t invented by the Perrins but it is unusual and a signature feature of both Coudoulet and their Grand Vin, bringing a richness, earthiness and tannic intensity that contributes to the age-worthiness of the wine. Each plot is hand-harvested and vinified individually, the grapes are heated to 80 degrees celsius to extract colours and flavours (thermovinification) before traditional maceration in cement vats for 12 days. The parcels undergo malolactic fermentation then are blended and aged in oak foudres for six months.

Given the general consistency of Rhône vintages, and the outstanding winemaking talents at Perrin you will struggle to find a poor bottle of Coudoulet. Marc Perrin himself says there is no such thing as a bad vintage, just different expressions of the winemakers art. I have tasted many vintages of Coudoulet at various maturities and they have all been memorable. As for ageing wine there are some that say you can enjoy Coudoulet young, but my recommendation would be to give it at least five years after harvest better yet ten. I had two magnums of the 2011 and opened one after 8 years: it was good without doubt, but the second I opened after 12 and it was a completely different animal; intense with a still-dense mouthfeel, some heft to those tannins, bold fruit notes of wild blackberry, black cherry and roasted currant, with lovely savoury elements of dark spice and game emerging across the palate and into the finish. It still had legs to go further in the cellar but I don’t regret opening it, unlike the 8 year-old-one. We were eating a great steak with peppercorn sauce at The Ox in Cheltenham (highly recommended) but Coudoulet will wash down a variety of roasted or grilled meat dishes. A desert island combination would be mature Coudoulet and a haunch of venison in blackberry sauce.

I do wonder whether longer ageing in new oak would give this wine even more puissance and longevity and make it more like its big brother but then what is the point of that? It is called Baby Beaucastel for a reason, and its difference is its strength. Its en primeur price has been creeping up in recent years but it is still eminently affordable especially for a wine of this pedigree, around £160 per 12 in bond, and looking around the web older vintages are readily available.

There is also a white which is equally as good but as ever with the Rhône it is talked about much less. It is made in much smaller quantities (only 3 hectares of vines) so is more challenging to source, and usually dearer, last release was £195 for 12. The blend is 30% Bourboulenc, 30% Marsanne, 30% Viognier and remainder Clairette all hand-harvested before a soft pneumatic pressing and clarification of the must. Fermentation is divided between oak barrels and steel tanks after which the wines is aged for 8 months before blending and bottling.

Rhône whites of this pedigree are know for their indiosyncratic ageing. You can drink the wine for the first few years after release and enjoy its forward, pure notes of spring blossom, white peach, fresh apricot and honeysuckle cut with a firm mineral edge and wrapped up with a lovely weighted texture. Then they have a tendency to shut down for a while and at that point patience is the key. Let the wine cocoon and you be rewarded as it re-emerges after a few years as a butterfly full of decadent, honeyed notes of roasted almonds, brioche, spiced marmalade and fennel seed, beautifully evolved and complex. The former will suit a variety of dishes from grilled scallops to roast chicken, the later I would be inclined to have with a platter of charcuterie, terrine, olives and cheeses.

Perrin wines always manage to hit the spot but Coudoulet for its price just hits a bit different. A true icon of the world of wine and a necessity in the cellar.

Written by A James Cole